I was born in Prestwick in February 1947, apparently one of the coldest and snowiest periods in living memory. During WWII, housing was at a premium and our family, along with our Aunt Peggy, Uncle Bob and cousin John, was squeezed into 14 Oswald Place Ayr, where we stayed until 1949. When 11 Pleasantfield Road became available, we relocated to the Toll and that became home for the next nine years. At the time, sister Kareen was 8, brother John was an infant and soon after we moved in, sister Ainsley was born.

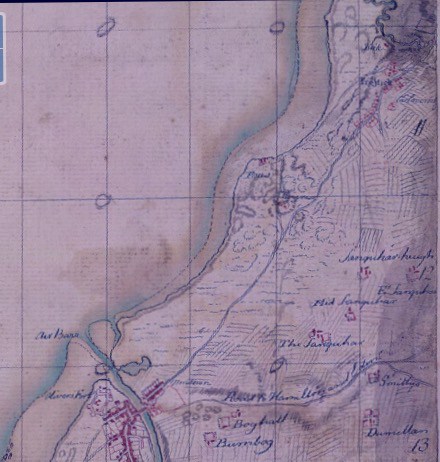

In the period 1470 – 1750 the area know as Prestwick Toll was sparsely inhabited sand dunes, poor quality land unsuitable for agriculture. Following the Jacobite Rebellion in 1745, William Roy of Carluke was commissioned to create military maps of Scotland. The lowlands were mapped from 1752-55. Roy’s maps are highly regarded for accuracy and detail. The map below shows the road from Ayr (then Air) through Newton to Prestwick. Just south of the area now known as the Toll, a small road branches off to the west, passing close to Kingcase “Spittal” and then salt pans on the coast, before heading north along the dunes back into Prestwick.

The salt pans shown on Roy’s map are not the same salt pan houses still standing on St Nicholas golf course at the end of Maryborough Road. Salt production had been practiced around this location since at least 1470 as noted in the Prestwick burgh records. Before Oswald’s pans were built in 1767 at the end of Maryborough Road, the Craigie pans at Bellrock cottage and Allison’s pans at Bentfield had been actively producing salt for “hundreds” of years. Salt panning is not at all easy and requires skilled salters as well as a rocky shoreline to store sea water in carved out pools filled at high tide. Also, nearby at Bellrock pit, there was a coal seam, which was the source of coal to boil the sea water. 20 tons of sea water were required to produce 1 ton of salt. All in all it was a labor intensive process. In those days, salt was an important commodity for the preservation of food, especially through the winter, when fishing was limited.

Kingcase Spittal, the ruins of which still remain on Maryborough Road, is of ancient origin, perhaps pre dating the old church ruins at Prestwick. The legend that Robert Bruce was cured of leprosy after he drank from a spring, resulting from thrusting his sword into the ground, (Bruce’s Well) and subsequently had Kingcase Spittal built around 1300 is probably wrong, as the original building could be much earlier. The burgh records make mention of problems with the lepers from time to time. In 1477 Andro Sauer had daily visits to his wife (contact with the lepers was prohibited by statute). On another occasion, there were complaints that the lepers were picking up driftwood and seaweed from the shore. The inhabitants of Prestwick claimed to have all rights to driftwood and seaweed.

The small branch-off “road” from the main Ayr-Prestwick road to the coast may well have been used for a thousand years, until 1839, when the railway cut it off. I often walked the surviving part from just over the railway bridge on Maryborough road to the Oswald salt pan houses.

Oswald’s salt pans were evidently a substantial investment in their day. It is also likely that the row of cottages near the Toll, known as the Maybole Row, was the first significant development in the area, just after the Toll house itself was built in 1769, following the Ayrshire Turnpike Act of 1767. Before the toll system, the roads were awful and only maintained by local folks. The issue of the day was simple, who should build and maintain the roads? The Turnpike Act was a major step forward. At first, the proposal was to build a new road bypassing Prestwick, but this was abandonded as it was too expensive. Another proposal was to build a dike, from Newton Loch to the Toll and also from the Toll to the sea, to prevent travelers from avoiding the toll. Again, this was never built.

Oswald’s salt pans needed a steady supply of coal from Bellrock pit. The Maybole Row was probably built as miners’ cottages, as it was only about 1/4 mile from the Bellrock pit and a few hundred yards from the main road (at the time all other buildings were along the main road)

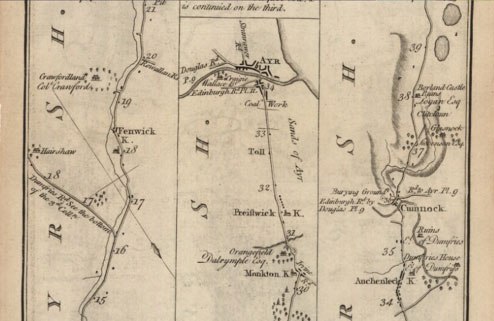

The Armstrong map of 1775 shows the location of the Toll, and the dotted road branching off just south of the Toll and along the same route as the earlier Roy map. This map also suggests that this “road” led to Irvine, by way of the beach across the Pow Burn. This was probably not a practical route, as tides and the flow of the Pow Burn could make it impassible.

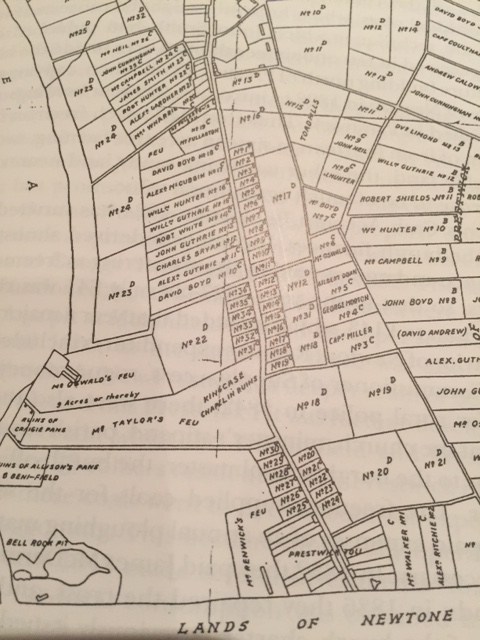

By the time the “Lands of Prestwick” were mapped in 1814 by Kenneth, Surveyors of Kilwinning, there were several cottages and a few two storey buildings along the main road at the Toll, as well as the Maybole Row. The area is shown as “Prestwick Toll” for the first time. Some attempts were made over the years to name the area as “New Prestwick”, but it was always known as “the Toll” when we lived in Pleasantfield Road.

An example of the Toll’s new inhabitants was James Wilson born at Prestwick Toll in 1814. He emigrated to Australia in 1841 and eventually founded Invercargill in New Zealand in 1857. The population of the Toll in 1814 was probably around 150 individuals. One of the houses along the west side of the main road was “Pleasantfield”. In the 1841 census, the family Logan is shown living at Pleasantfield.

The 1814 map also shows a road running west from the main road just north of the Toll to between the ruins of Craigie pans and Allison’s pans. Again the railway cut through this older road and the present day Maryborough Road, with a new railway bridge becoming the route connecting the main road and the coast. These coast “roads” were nothing more than sandy tracks, Oswald complains that the carts could not take more than a few hundred pounds of coal or salt over the poor roads.

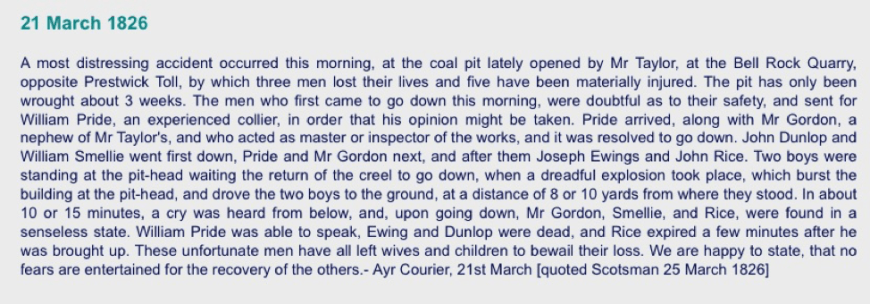

Coal mining was an important activity around the Toll in earlier times. In 1820 an accident at the Ann coal pit near Prestwick Toll resulted in the death of a miner Bob Humphry (17) . A roof timber collapse resulted in burial under rubble.

Prestwick Toll, as well as most communities in the west coast of Scotland, experienced a large influx of Irish emigrants in search of economic opportunities and escape from various potato famines. The 1841 census is the first time we see the families living at the Toll listed by name, occupation, age and place of birth. Of the 78 households listed, 42 have heads born in Ayrshire, 26 born in Ireland and 10 born in other counties of Scotland. There were 313 inhabitants. The occupations are dominated by weaving (47) and coal mining (28). Many of the weavers came from Ireland. Also the expansion of the rail network and the opening of the line from Glasgow to Ayr in 1839, with stations at Prestwick and Newton, made it much easier for goods and people to flow into the area.

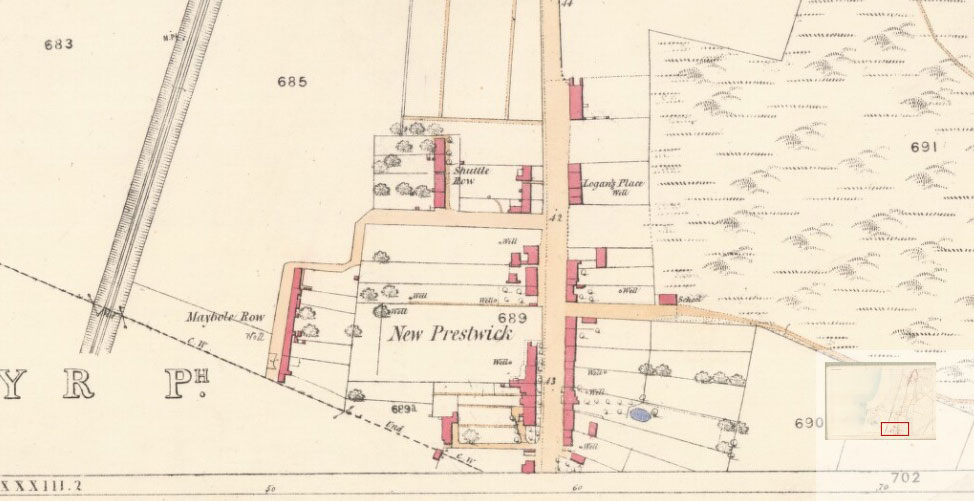

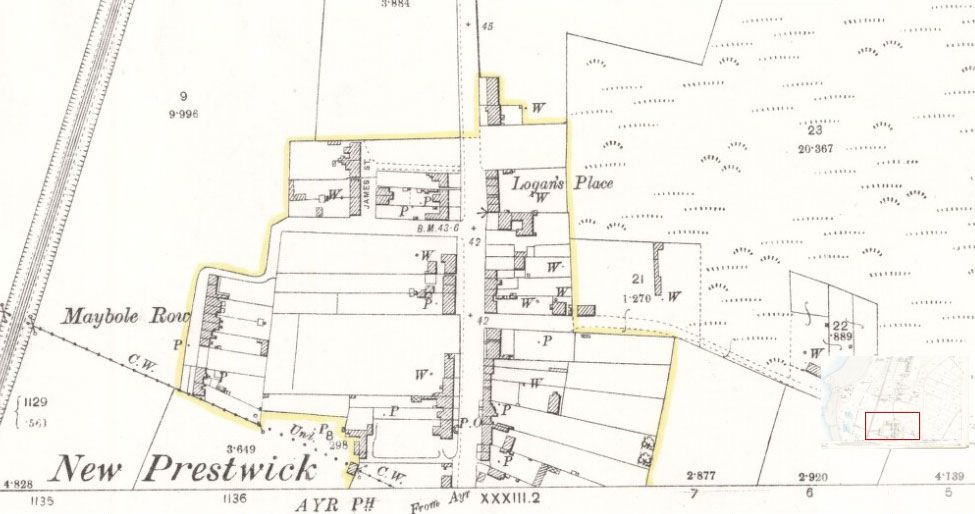

The start of the Ordinance Survey maps dramatically improved the historical record of structures and roads. The first OS map of Prestwick Toll in 1855 shows the Maybole Row, Shuttle Row, the buildings along the main road and the railway line, all very accurately set out.

The comparison of the 1851 census with the 1841 census highlights a significant shift in occupations. By 1851 there were only 12 coal miners. Hand loom weaving was the principal occupation with 53 weavers living at the Toll. Of the 315 inhabitants, 39% were born in Prestwick and 12% in Ireland. The house “Pleasantfield” was occupied by a Glasgow man, his wife, daughter and two grandchildren, who had been born in India. Presumably the Logans had relocated into Logan’s Place on the main road.

The railways revolutionized transportation, and road travel went into decline. The Toll was closed in 1878 and road maintenance was taken over by the local authorities.

A comparison of the 1855 and 1892 OS maps of Prestwick Toll, shows that there was very little development during this period. The local coal mines were closed, salt production ended and hand loom weaving was being replaced by factory weaving.

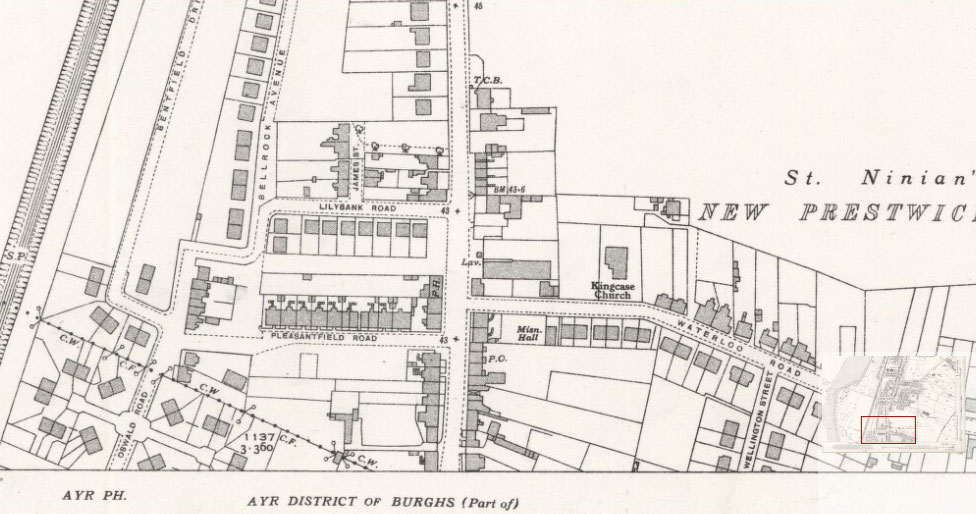

The next OS map of 1908 shows new buildings at Pleasantfield Road, part of Waterloo Road and north along the main road. This first Plasantfield Road was a single row of two storey houses, with a fire break between No 9 & No 11. The individual house units were relatively small. No 11 was roughly a family room 14’x14′, a bedroom 12′ x 8′, a “good room” 12’x12′, and a scullery 10’x6′ with a single sink with cold running water. The toilet was outside on the landing and shared with the family next door. The family room had two alcove recesses (with curtains) for beds. Four of the house units shared a wash house which had a big tub that could be heated by a coal fire and a wringer to partly dry the washing. Wash day was Monday and the whole drying green opposite the houses was full of drying washing on lines.

The houses were heated by coal fires in two of the rooms.

Just after (the first) Plasantfield Road was built, my grandfather, grandmother and four aunts moved into No 3. Soon after my father, also named Jim Mitchell, was born in 1915 and grew up at the Toll. He was known as Jimmy Mitchell.

My grandfather (also Jim Mitchell) was born at Glenngarnock in 1879. He moved to The Toll when he was about 35 and remained a Prestwick resident until his death age 94. He was born before electricity, before air travel, before cars, yet he lived to see a man land on the Moon.

Following WWI, my grandfather planned on relocating the family to the United States. He was an electrician in Annbank No 9 coal mine. Following the miners strikes in 1926 and 27, he obtained an immigration visa in Glasgow, on Feb 4 1928, and sailed from Greenock three weeks later on board SS Andania. He worked as an electrician in a steel mill in New Jersey for a few years. Unfortunately the Great Depression thwarted his plan to bring the family to the US and he returned to Prestwick Toll in 1933.

By the time of the OS map of 1938, the Toll was essentially the same as I remember it in the 1950s, with the exception that the Maybole Row had been demolished. I remember the remnants of the foundation slabs in what was a waste area field while playing there as a child. There was virtually no development or building during WWII.

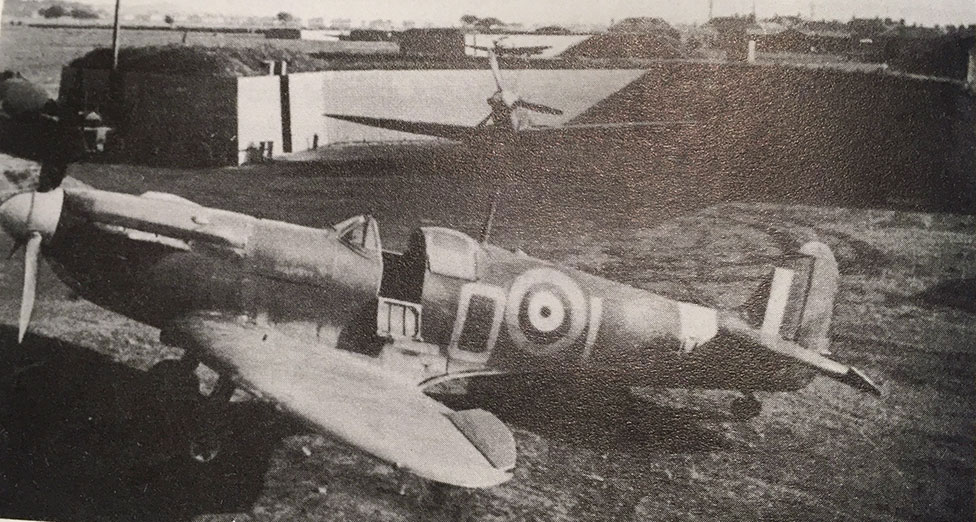

My father lived in Prestwick virtually all of his life except for his retirement years in Alloway. He died in Ayr age 91. In growing up at the Toll, he remembered playing with the other children in an area known as Robertson’s field, which was west of Pleasantfield and bordered by a wall called the “tarry dike”. Games were hunch cuddy hunch, relievio and football. He attended primary school at Kingcase church hall, Prestwick Public until age 12 and Prestwick High until age 14. He was a milk boy for Cowans Dairy 9-14 and an apprentice joiner 14-19 at Thompson & Blackwood. As a skilled carpenter he was called up in 1939 (age 24) to train in Glasgow working on Hurricanes and later in the war, repairing Liberators and Spitfires.

He played football for Crosshill and had a trial for Ayr United before the war ended all sport. After the war, he eventually became Managing Director of Scottish Avation.

In 1949, my “big sister” was 8 when we relocated into No 11 Pleasantfield Road. Her primary school was Heathfield, which had been built in 1931. At a very early age she developed a strong interest in dancing. She saw a picture of a little girl called Marigold Roy in the Ayrshire Post and managed to persuade mum to enroll her in Sally Roy’s Belmont School of Dancing. She attended Prestwick High 11-15. Ballet then became full time, when she attended the Lillian McNiels School of Ballet in Glasgow. She became ARAD and passed exams in advanced ballet. She opened her first dancing school in Berelands Hall age 20. Prestwick School of Ballet was born. She later opened ballet schools in Troon and Cumnock. Eventually she developed Dansarena in Ayr and had a ballet school in Dumfries.

My “wee brother” John and I ran around the Toll for what seemed like an eternity, but in actual fact it was only 9 years. In those days, doors were seldom locked and children safely roamed the district from dawn to dusk. There were few cars in the streets. We had good friends Billy and Jimmy Campbell and Bobby and Findlay Fleming, who were often part of these childhood adventures. We played extensively in the “Old Field” which ran parallel to Pleasantfield Road with billboards at the main road end and open into a field at the other. McClean (one of the families) had a hen run and a maintenance yard which separated the Old Field from the backs of the Pleasantfield Road houses. The hen run backed up to the original Toll Bar. There were two dust bins for every house, one was called a “pig bin”, and had all the food scraps. The other was mostly for ashes from the fire. McClean would empty the pig bins several times a week and feed it to the chickens. There were a few stumps of trees in the old field which all the boys used as imaginary “aircraft” flying sorties in our make believe world. The billboards were about 20 ft high, and had a lattice framework, ideal for climbing. A daredevil feat was to walk along the top which was about 4″ wide, to the amazement of the women shopping on the main road.

Several times a week, a horse drawn flat bed cart, run by Dobbie, passed along the road, stopping at every close. The cart was full of locally grown produce, still with the dirt on the potatoes, carrots and so on. Families would buy what they needed fresh for the day. Milk was delivered every morning in pint bottles from Cowan’s Dairy, just across the main road. The top 20% of every bottle was cream. At Heathfield School, we also had 1/3 of a pint of “free” milk every day at morning play time.

Onion Johnnys would arrive from Britany or northern Spain at Ayr and cycle around the town for weeks, until their big pile of fresh onions were sold. Then back on a boat from Ayr and home. How could it make economic sense to grow onions in Spain, bring them to Ayr and cycle around town until they were all sold? But sure enough, it was one of the graphic memories growing up at the Toll.

On the main road, Tommy Hill had a grocers shop where we often went for butter, cheese, fresh rolls, eggs and so on. The butter was in massive blocks which Tommy would carve off with wet wooden tools, then pat it into a little block and weigh it. The shop also had great sacks of loose tea which would be scooped out and weighted using traditional brass balance scales. Hams and several kind of meats were sold sliced. The slicing machine was hand cranked and everything in the shop had a fantastically fresh aroma. Once Tommy made your change, he would clap the coins onto the glass counter with one hand, and have his other hand empty while making the same move —- and then uncovering his hand with no coins, disappeared by “magic”. Tommy would get a great kick out of fooling us. One amazing memory was that there were several dogs who would “go for messages”! These dogs could be seen walking by themselves, with a basket in mouth, often to Tommy Hills. In the shop, the dogs would get in the queue and wait to be served. Then Tommy would take the note from the basket, fill the order, take the money, put the change in the basket and off the dog would go back home!! This was so common that people just took it for granted.

Just north of Tommy Hills was Dixon Black the chemist, a very proper classical little shop. Just south of Tommy Hills was Fraser & Tuckers, newsagents (I had a paper delivery round there when I was 11, paid 10 shillings per week (50p)). Farther along the main road (Ayr Road) was Climie the butchers.

Next door to Climie was Peter Logan, licensed grocers then Willie Graham’s carters yard and Mayfield house. Willie Graham operated horse drawn carts even after WWII when petrol was scarce. He had a contract with Scottish Stampings and others to remove waste and dump it on the Newton Shore.

Below, Graham’s carts on Newton Shore.

Across the main road from Waterloo Road was the original Toll Bar, a real traditional drinking spot. Also seen beside the Toll Bar are the Bill Boards that we would climb as children and walk along the top.

At the corner of Pleasantfield Road was Mrs Low’s corner grocers shop. Even though it closed at 6.00 pm, we would often chap the back door to get a tin of peas or sugar or whatever was short. Mrs Low never took any money from the children, she just kept a little book.

Two sisters, Ellen and Rosie Hay operated the little Post Office just south of Lows. I remember starting a saving account there by buying “stamps”.

Along the road from the Post Office was Sanny Hamiltons the butcher and Willie Cuthbert the barber. The butchers was an amazing place with half cows hanging on hooks ready for cutting up and hand cranked mincing machines for various sausages. We had our hair cut every two weeks at Cuthberts, another classical old-time shop.

Just north of Waterloo Road was the Bus Garage (later Seatons), Ferrie Place, Cowans Dairy and Logan Place.

Along the main road into Ayr was the Regal Cinema which was a great attraction on Saturday mornings for the local children.

A major adventure would be walking up Waterloo Road, then heading north in rough ground, past some allotments and into the abandoned airfield. Heathfield had been developed into a base for a squadron of spitfires and Hurricanes during WWII. We would siphon aviation fuel out of the disused underground fuel tanks one jam jar at a time.

The Merlin engines used in Spitfires and Lancaster bombers were so critical to the war effort that a shadow factory at Hillington in Glasgow was built to increase the output. Scottish Stampings produced the forged crankshafts for the Merlins at Hillington.

There was a great celebration in the drying green in 1953 to celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth. Picnic tables were set out, there were games and races and prizes for all the children. The day ended with a big bonfire after dark. I was 6 so I was “in bed”, but I cried so much to get to see the bonfire that my parents dressed me and let me run to the fire which was directly across from No 11. Just as I sprinted across the road, a burning cardboard box blew off the bonfire and a piece of it hit my neck. Off I went running home crying, within an instant of leaving the house, and from that day to this I was accused of running right into the fire in my excitement. (The burn was not serious)

Wee brother John had a rough and tumble childhood, climbing on Tommy Burgges hut roof, often playing on the beach, swimming in the sea, playing on the railway, playing at the quarries, climbing trees in the orchards, building bonfires on Guy Fawkes night in the endless days of our childhood. He had a good friend, Jimmy Brookes who eventually joined the army. John eventually joined the Royal Marines and had a long and successful career specializing as a leader in mountain and Arctic warfare. After completing a 23 year career in the Royal Marines, the latter part of which was spent in special forces, John went on to graduate from Strathclyde University with an honors degree in economics.Tommy Burgges hut was a landmark wooden hut, opposite #7 Pleasantfield Road, with a large wooden boot hanging over the front door. Tommy was a most excellent cobbler and worked in traditional leather shoe mending techniques.

The street was lit with gas lamps. At dusk, a lamp lighter would cycle along with a long pole like a lance and try to trip the gas valve as he passed by on his bike. After he was gone, we would sometimes shimmy up the lamp post and turn the gas off so we could play hide & seek in the dark.

Heathfield School was a short walk from the Toll, or in my case a short run. Bill Nichlson often sat in a wheelchair at the top of the road at the corner of the main road. I would come running down Waterloo Road at full tilt and straight across the main road down Pleasantfield without stopping for a look, or so he thought. I actually did glance at the traffic and just sprinted through a gap. Somehow, Heathfield had developed a reputation for being the best primary school in Ayr and Prestwick. This may seem a little surprising as the children were all from the surrounding areas which were far from affluent. On reflection, I do believe that the primary education was very good and that it was the culture and quality of the teachers that made it so. Heathfield’s teachers drummed into us the importance of honor and manners. We were told to get up and offer our seat on a bus to an older person and to act in a manner that made us proud to wear that scarlet cap, so others would say “see, that’s a Heathfield student”, what a nice child. There were around 42 students in each class. From primary 1 age 5 to primary 7 age 11. All the children were “lean” and ran around like a swarm of bees at the play times. At the end of each play time, a teacher rang a big hand bell, and suddenly there was silence as lines formed for each class. Once the lines formed, there was no talking. Each class marched in order to their rooms. Once in class, there was no talking. We practiced hand writing using little ink wells on each desk and nib pens, what a mess! Questions could be asked by raising a hand, otherwise silence in class was the order of the day. The better performing students were placed in the back of the class, and the poorer students in the front. Class started at 9.00 am every day with the Lord’s Prayer. A lot of the learning was by “chanting”, for example the times tables up to 12×12. Every child knew how to multiply up to 12×12 in their heads as it was drummed into us. Besides, the money we grew up with, 1/4, 1/2, 1, 3, 4, 6 penny coins, 1, 2, 2&1/2 shilling coins, 10 shilling note and 1 pound note required a good understanding of basic arithmetic in order to figure out change!

We were one of the first families in the road to get a TV. Probably around 1956. There was one channel, and the local children would gather on the floor at 5.00 pm to watch a show for a little while before being chased home for “tea”. Also, my granny Crorkan and Aunt Peggy would visit mum to watch Norman Wisdom on TV, these were always very exciting visits.

Halloween was a magical time. We made our own costumes and went around the neighbor’s houses doing party pieces, and received some nuts or a toffee apple or home made tablet. There was no candy or sweeties, everything was home made.

The children celebrated Easter by painting hard boiled eggs and rolling them down the hill at Kingcase. We also received a few chocolate Easter Eggs, which were a major treat.

I took my first job as a paper boy with Frasers aged 9. Later to become Fraser and Tuckers, I was a paper boy for 5 years.

Bertie’s at the corner of Heathfield Road and the main road had great ice cream and chips. A classic Italians fish and chip shop, it was always a treat to get a bag of chips there.

Wee sister Ainsley was born in 1951 and lived at No 11 until the family relocated to Overdale Crescent in 1958. She has lived her entire life in Prestwick. She started Twix n Teens a shop in Ayr specializing in sports and dance wear.

The council of Prestwick provided every child with a voucher book each June when school broke up for the summer. The vouchers were eagerly awaited and allowed each child all kinds of free activities including a donkey ride on the beach, ice cream, entry to the swimming pool, stage coach ride, putting green, cinema and Dukw ride.

After Heathfield, I attended Prestwick High and the Gresham House in Motherwell. I worked at Scottish Stamping and Engineering as an engineer. I graduated from Strathclyde University in 1972 in mechanical engineering. I married Margaret Easdale from Prestwick and we emigrated to the USA in 1982. I started a number of engineering companies in the US and am now retired in Florida.

The original Pleasantfield Road was demolished in 1968, as the housing was deemed sub-standard. By today’s standards, these houses were way short of acceptable, yet the families who lived there made their world a perfectly safe and acceptable place. No one complained that somehow they had a raw deal in life and that their housing conditions were holding them back.

As has been said, the Toll gave me more than it ever took away, and provided me with a good value system for life. Even though there was little to go around, and I remember the ration books that were used for some scarce items almost ten years after WWII, somehow all the families helped each other, everyone had an open door and a smile for you. There was virtually no crime and our childhood was a happy and carefree time.

Families Living at Pleasantfield Road in the 1950s

- #1 ground floor (GF) Rowan, Woods, Gibson, Scott | upper floor (UF) Tierney, McKays, Dunlop, Morrison

- #3 (GF) Mitchell (grandfather), Holmes | (UF) Briggs, Bruce

- #5 (GF) Rennie, Blane | (UF) Ridler, McClean

- #7 (GF) Kerr | (UF) McCormack

- #9 (GF) Agnew | (UF) Ralph

- #11 (GF) Cooper, Girvan | (UF) Mitchell, Kerr

- #13 (GF) Neville, Alcroft | (UF) Davidson, Joel

- #15 (GF) Taylor, Guthrie | (UF) Flemming, McClean

- #17 (GF) Smith, Hodson | (UF) Campbell, Galloway

- #19 (GF) Nicholson, Morrison | (UF) Seaward, Forsyth

- #21 (GF) Paton, Kerr | (UF) Kennedy, Nichol

The Logans of Pleasantfield, Prestwick Toll

by Alison Logan

The Logan family were a presence at Prestwick Toll for about eighty years, from the early 1820s until after my great grandfather James Gordon Logan died at Pleasantfield House, Prestwick Toll in 1903.

Records show that on February 21st 1821, John Ronald Logan and his wife Elizabeth McNeil were “seized” of “1 Rood and 28 falls of ground on the west side of the High Road from Ayr to Prestwick, and 2 Roods and 16 Falls of ground at Prestwick Toll, being part of the Common of Prestwick with houses on the said subjects”. It sounds from this that there were houses on both plots of land and probably the first on the West side became Pleasantfield House where the family lived, while the other, probably the “Logan’s Place” marked on old maps of the area, was rented out.

So in 1821 the family had the resources to buy a substantial property which provided them with an income for the rest of their lives but this was not always the case, and their good fortune came about in a curious way.

John Ronald’s early life is a mystery. He stated that he was born in Glasgow in 1775, to John Logan Landed Proprietor and Jane Campbell. No such birth is recorded but there is circumstantial evidence that he was the illegitimate son of John Logan of Knockshinnoch near Cumnock who was in Glasgow in 1775. John Ronald seems to have been brought up in Ayr and was apprenticed to a cabinetmaker which in itself suggests a family of some means, as apprenticeships at the time had to be purchased. On completing his apprenticeship, he was conscripted into the Ayrshire Militia. He seems to have taken to army life as he stayed in the militia for 17 years (1797 to 1813), long after his compulsory service ended, rising to the rank of Sergeant. For most of this time the militia was on active service due to the wars with France and John Ronald travelled throughout the UK and Ireland with the regiment. By the time he left the militia in 1813 John Ronald had been married ten years and had had four children. He married the eighteen-year-old Elizabeth McNeil in 1803. A wise move as it turned out.

During the early years of their marriage the couple lived with Elizabeth’s mother in Ayr. John Ronald is recorded as either a cabinet maker or later on as a “wright” which suggests carpentry rather than fine furniture, was his trade. Then in 1817 an event occurred which was to change their lives completely. Elizabeth had a much older half-brother, John Gordon, the result of a long but unmarried relationship between Elizabeth’s mother and Alexander Gordon, Surveyor of Customs at Ayr. This John had managed to join the Excise Service and had a successful career, eventually rising to become Keeper of Excise on the Island of Islay. Then in 1817 he suddenly died after an illness of only five days, leaving no will. He had wanted his estate to go to his half-sister but there was a problem. A bastard was assumed to have no relations except his mother (by this time dead) and a spouse and children (he had none) and if there was no will, the estate reverted to the Crown. Those who claimed an interest in a Bastard’s estate had to petition the Government who would decide how to apportion the money. Unexpectedly, as well as Elizabeth McNeil there were two other claimants for John Gordon’s money. One was an aunt who was only claiming a small amount but the other were the powerful and well off Ayr family, the Limonds, who claimed at least half. They based their claim on the fact that their mother had also been the child of Alexander Gordon by another mother. The Limonds tried to take advantage of the inexperienced Logan family to get them to drop their claim or at least to share the estate. In the end, their efforts failed; they were awarded nothing and the bulk of the estate, about £1000, went to Elizabeth McNeil but there are hundreds of pages of evidence of petition and counter petition in the Archives which give fascinating insights into both these families.

Thus by 1820, the Logan’s have access to money which will have been greatly welcome as by now they have had eight children, of whom six are alive. Shortly afterwards they bought the land at Prestwick Toll. It is not known when they actually moved there. The births of their remaining four children are all recorded at Ayr but it is likely that they were actually born at Pleasantfield. John Ronald was still describing himself as a wright in 1830 when their last child was born in 1830 (27 years after their first!) but by 1837 Pigot’s directory of Ayrshire lists him under “Nobility, gentry and clergy”. Next to John Ronald in the list is David Limond, Provost of Ayr. A juxtaposition which I hope gave him some satisfaction.

After the move to Pleasantfield, the Logans sought a good career for their eldest son John who was an intelligent and personable lad of about eighteen. In the autumn of 1822 he left for Edinburgh and medical school, a journey of five days which he vividly described in a letter home to his parents. After graduating, John joined the East India Company’s army as an assistant surgeon and set off for Calcutta. It must have been about this time that his parents had his portrait painted which is still in the family. Sadly, his career was to be a short one as he became ill in 1827 and died on his way home.

The Ayr Advertiser of 8 May 1828 carried the following announcement:

“In December last, on his passage home from Bengal, assistant surgeon John Logan of the Hon. East India Company’s service, in the 24th year of his age. He was a young man of whom the highest expectations might have been formed and it is some consolation to his friends and connections, if anything can at all console them for the loss, that he was beloved and respected during his honourable but short career”

This loss of their eldest son must have been devastating for John and Elizabeth but they had seven living children and one more still to be born. What happened to the rest of these children? The second son William certainly had an interesting and long life. William followed his brother John to India and became and indigo planter in what is now Bangladesh. In 1838 he gave John and Elizabeth their first grandchild with the birth of Emma, followed by William two years later, both it is assumed to an Indian mother, as only the father is listed on the baptism records. In the 1841 census William is at home with his parents in Pleasantfield with Emma only, having left baby William in India. During his stay in Scotland he married Isabella Dick and the couple returned to India with Emma in 1842. Their only child Andrew was born in Mymunsing India in 1843 and Isabella died of fever there in 1845. Shortly afterwards William returned briefly to Scotland with all three children. He tried to set up in business as a stockbroker, but the business was not a success and he was declared bankrupt in 1850. Shortly afterwards, leaving the children with their grandparents and aunt Isabella, William set off again to find fortune abroad, going first to Australia and then finally to New Zealand where he settled as a farmer, married again and founded a new family. Once established in New Zealand, William made arrangements for his surviving children, Emma now seventeen and Andrew to join him.

What happened next made headlines round the world. This from the New Zealander of July 2nd 1856

“ Sinking of the Josephine Willis – On Sunday last a most appalling catastrophe occurred in the Channel, resulting in the total loss of the fine ship Josephine Willis bound for Auckland. About eight o’clock in the evening, when five miles for Folkestone, this ill-fated vessel was run into by the iron screw steamer Mangeron and in a very short time the Josephine Willis foundered, most of her passengers, amounting to about sixty persons, and a crew of thirty, we grieve to relate, met with a watery grave”

A later edition records this:

“One of the most distressing episodes of the wreck was the drowning of two of the children- son and daughter – of Mr W R Logan of Otihuhu. They had been left in Scotland to finish their education and were on their way out, in charge of the captain, to join their father at Auckland. The young lady, aged seventeen, was well nigh saved, as two passengers and one of the officers gallantly rescued her when the ship went down and got her to a spar. However, after clinging to it for some time Miss Logan succumbed to exhaustion and was swept away as the sea broke over it.”

By the time of the tragic drowning of his grandchildren, John Ronald was over eighty and most of the family’s affairs were being looked after by my great grandfather James Gordon Logan, the only surviving son who was not abroad. James was pursuing a successful career as a merchant in Glasgow and had a family of his own but often visited Pleasantfield and , it is clear from his letters, was responsible for the financial affairs of his far flung relations, a duty which he shouldered with acceptance and resignation, although his weariness of the task sometimes shows through. Over the years correspondence went to and fro with New Zealand where, as well as his elder brother William, his nephew and eldest son were also now settled.

John Ronald Logan 1775 – 1858

John Ronald died in 1858 at the age of 83. Elizabeth lived on in quiet retirement at Pleasantfield for a further seventeen years with her daughter Isabella looking after her, until her death in 1875. Both John Ronald and Elizabeth are buried in the churchyard of the Auld Kirk at Ayr. After 1875, Isabella was the only permanent resident at Pleasantfield although the Glasgow family continued to stay there for extended periods. Isabella is mentioned from time to time in my great grandfather’s letters to New Zealand and he comments that she is “getting rather stout”.

Elizaeth McNeil as a very old woman

Isabella Logan, almost certainly Pleasantfield House’s longest resident. She lived there from the early 1820s until 1898.

Isabella died at Pleasantfield in 1898 and for the last few years of our family’s association with Prestwick Toll, the house seems to have been used as a holiday home. My great grandfather James Gordon Logan died at Pleasantfield in 1903 although his permanent home at the time was in Stirling. The last two valuation rolls which are available, for 1905 and 1915, give a glimpse of what happened next. In 1905 my great uncle Bob (Robert Wilson Logan) is listed as the tenant of the Pleasantfield property with no mention of the land on the other side of the road which must have been sold. By 1915, it looks as if other buildings have appeared alongside Pleasantfield House as the property now consists of 4 houses and a shop at “Pleasantfield Place, Ayr Road”. Uncle Bob is probably the tenant as my grandfather John Gordon Logan, his elder brother, was living in Egypt at the time. This gives me a personal link to Pleasantfield as, although I never met my grandfather, I do remember Uncle Bob, a tall, kindly, and distinguished looking elderly gentleman with a distinct twinkle in his eye. He never married and lived with his two unmarried sisters for the latter part of his life, having retired from his career manufacturing fishing nets in Aberdeen. Sometime after 1915 Pleasantfield must have been sold and the Logan’s association with Prestwick Toll came to an end, although I don’t know exactly when this was.

Although the Logans were at Pleasantfield for over eighty years, there is little evidence that I have been able to find that the family were deeply involved in the affairs of the community at Prestwick Toll. In 1832, John Ronald is listed as voting for the Whig candidate Mr Oswald in the General Election which followed the Great Reform Act of 1832, one of only 42 electors in the parish of Monkton and Prestwick. Beyond that, I have turned up no references at all. Perhaps they are out there somewhere as it would be good to think that the family made a contribution to the local community they lived amongst for such a long time. What I do know is that they kept a strong connection to Ayr, where John Ronald was admitted as a Burgess in 1822. The Logan boys all went to Ayr Academy and did well there as their medals show and, as far as I know, the family continued to worship in Ayr.

James Gordon Logan 1824 – 1903

Robert Wilson Logan 1867 – 1953 in his French Red Cross uniform in 1915. He was too old to fight but joined the French Red Cross and drove an ambulance on the Western Front.

Ayr Academy medals awarded to various Logan boys including, top right, a gold medal for Latin won by James Gordon Logan in 1839